Since the beginning of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration (AMLO), a package of infrastructure projects has been announced with the aim of promoting the country’s economic development, among which are the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Interoceanic Corridor (CIIT) and the Mayan Train (TM).

Despite being presented as independent projects, one focused on boosting tourism and the other on increasing the flow of goods through the ports of Coatzacoalcos and Salina Cruz, both are part of a regional megaproject that seeks to fulfill the intention that various governments in the past have had to exploit the natural resources, biodiversity, as well as the geographical and climatic conditions of southern Mexico.

In a press conference, the Ministry of Economy stated that with the bidding of the industrial parks of the CIIT, “a project conceived since the 19th century is materializing… [which would be] …a trigger for economic development and welfare for the people of the southeast, where what we seek is to generate more jobs, better-paid salaries, dignified wages, and also companies committed to the community.”

According to official sources, this is an opportunity to benefit the region from the growth and economic development that will be generated with the presence of industries and increased trade. From this perspective, the federal government expects the economic spillover to be sufficient to benefit the population residing in the region. However, various studies and analyses have also highlighted the impacts that these projects will have on people’s lives, the natural, cultural, and historical heritage of indigenous and similar communities inhabiting the territories where they will be installed, as well as the aggressions and harassment faced by land, territory, and environmental defenders.

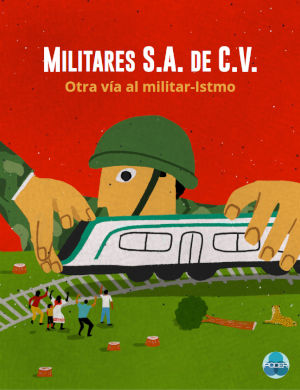

This report aims to update the information contained in “The Elites Train: Beneficiary Companies and Energy Projects in Southern Mexico,” published in spanish by PODER in 2020, a document that identifies and shows which corporate and business actors are involved in the Mayan Train project. Additionally, it seeks to demonstrate that this infrastructure will have a direct impact on the supply chain for industries and will fall under the responsibility of the armed forces to ensure security conditions for investments through controlled management of the territories.

From this perspective, the arrival of the armed forces not only as builders of the projects but also as administrators, owners, and managers of both the TM and the CIIT, and what it implies; that is, control of state-owned enterprises, coordination and management of projects, power over the granting of contracts with private companies, as well as territorial management. This role of the armed forces generates uncertainty as these are considered priority projects, of public interest, and national security.

Hence arises the following question: Does the control of megaprojects by the armed forces guarantee proper business conduct, including respect for human rights, and prevent phenomena such as the capture of the state by corporate elites?

The federal government has emphasized that the National Army and the Mexican Navy are honest institutions respectful of human rights.

Based on experience and precedents in Mexico, the presence of the armed forces in tasks that usually fall under civilian authorities generates a well-founded fear that transparency, accountability, and human rights may be affected. This is relevant given that the TM has already violated various rights such as the right to free, prior, informed, and culturally appropriate consultation, in addition to being a project designed from a development perspective that benefits large companies and the extractivist model above individuals and communities.

For the preparation of this investigation, the sources were the press releases and progress reports of the federal government, as well as the databases of contracts from the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (SHCP), Compranet, and contracts from the Federal Electricity Commission (CFE). Likewise, there was a review of the decrees and declarations of public utility of the Official Gazette of the Federation (DOF) and the annual reports and financial statements of the companies participating in these projects.

Visit El negocio del Tren Maya.