-The Mexican State, since the period of repression following the Tlatelolco massacre, has allocated public funds to investigate, pursue, and spy on feminist groups. As stated by the current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, these groups have attempted to “impact his government.” However, no one within the state apparatus explains the actual utility of this persecution.

- Please visit the microsite (complete reports): “What the waves did not tell us” by COCE.

Documentary evidence stored in the National General Archive (AGN, by its acronym in Spanish) originating from the intelligence bunkers of the Federal Security Directorate (DFS, by its acronym in Spanish), as well as information extracted from the #GuacamayaLeaks leak related to communication systems (emails and security reports) of the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA, by its acronym in Spanish), reveals half a century of government surveillance against feminist women’s groups and certain LGBT+ community groups in Mexico.

The context of espionage and violence against self-proclaimed “leftist or communist” groups in Mexico, following the emergence of the so-called “Brigada Blanca” (White Brigade), has not changed, even with the arrival of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador from the MORENA party.[1].

This operation, the Brigada Blanca, was established by the Partido de la Revolución Institucional (PRI) to carry out operational tasks of State Terrorism under the government of Mexico, orchestrated by the national security apparatus of the former president, Luis Echeverría Álvarez, against members, relatives, and friends of opposition groups during the period of repression. It was particularly targeted at the operations of the Liga Comunista 23 de Septiembre (LC23S).

A wrongdoing that doesn’t fade away with the years. Despite the passage of time, half a century, the National Defense Elements (current and some retired), organized themselves to pursue feminist associations and collectives: from their workplaces, schools, or recreational centers to their homes. All with the aim of extracting information that could serve the state as a strategy to counteract social movements.

Specifically, the documentation analyzed by the Colectivas Organizadas Contra el Espionaje (COCE) (Organized Collectives Against Espionage) – of which PODER is a member and co-founder – begins with strategic profiles of the first feminist groups in the country, recorded in 1974. It concludes at the end of 2019 with the revelations from the “Guacamaya” hacker group to which this collective had access.

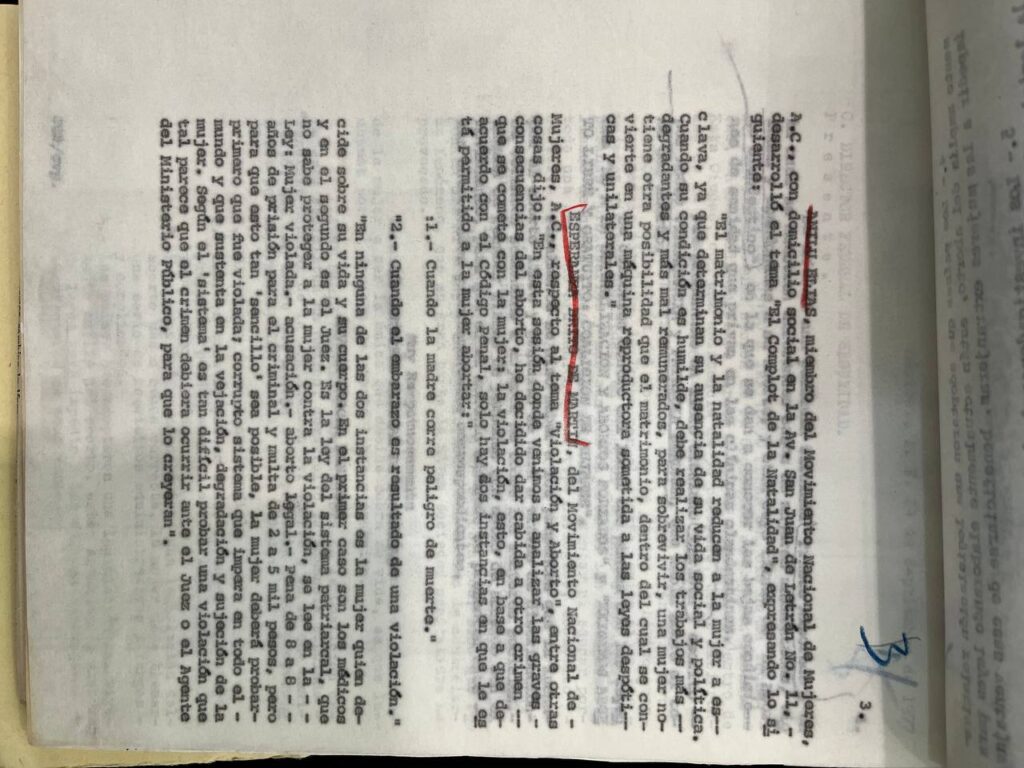

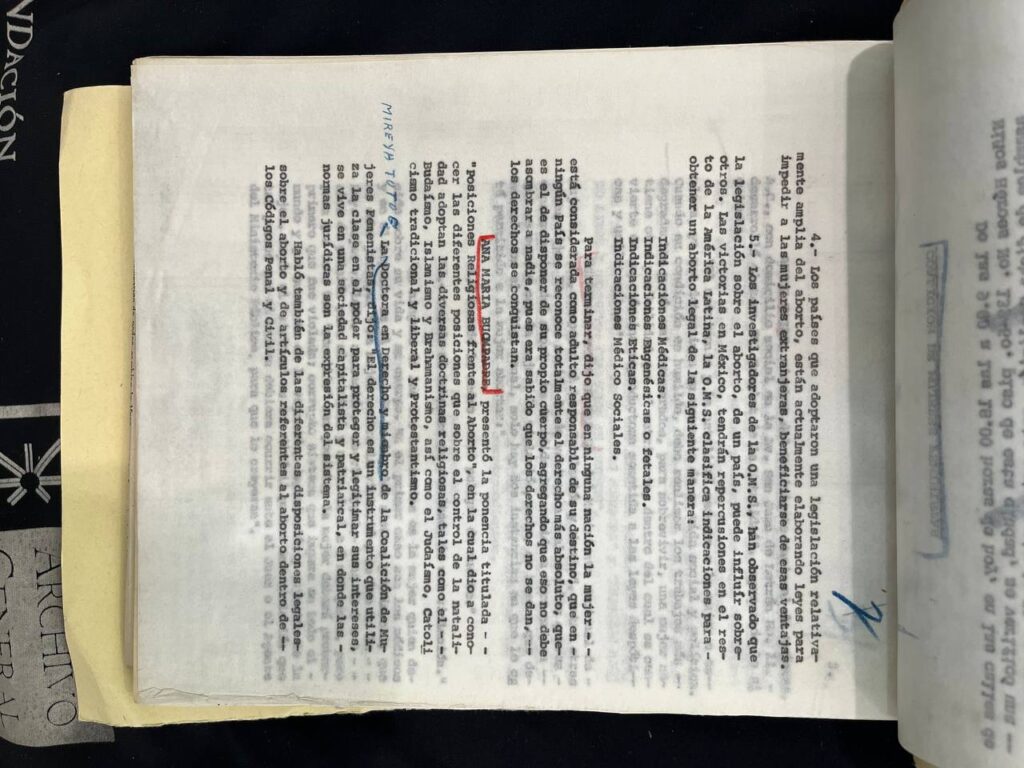

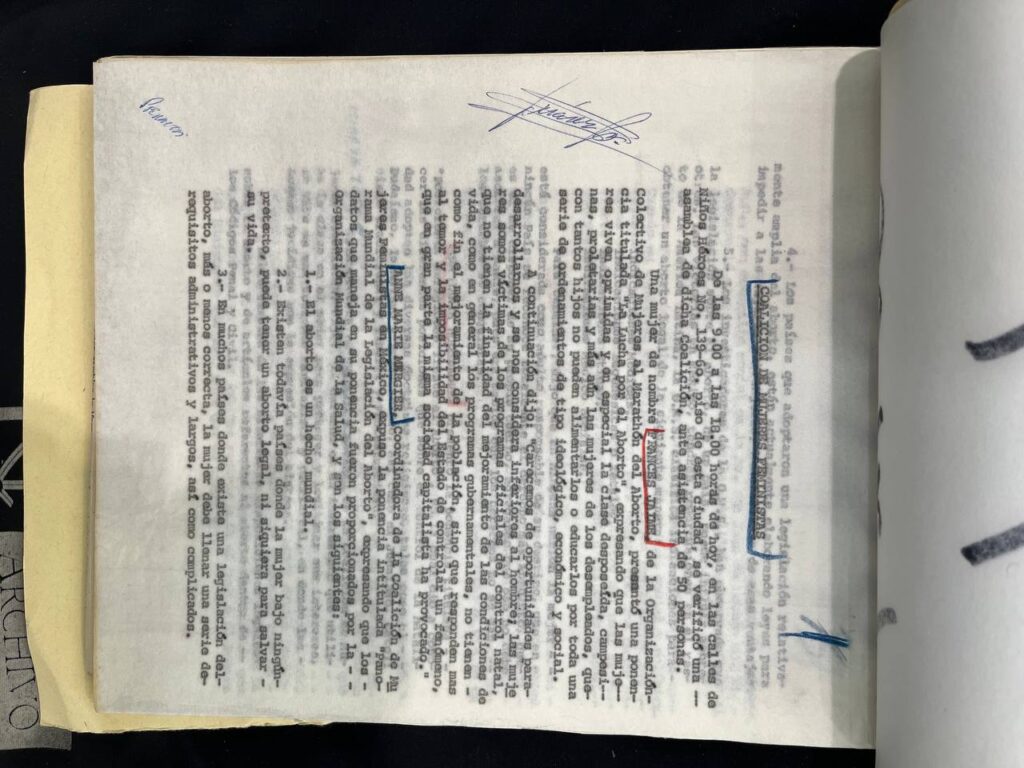

Regarding the analysis of the Federal Security Directorate, given the temporal context, it was concentrating efforts on gathering information about all activists who were part of groups advocating for legal abortion.

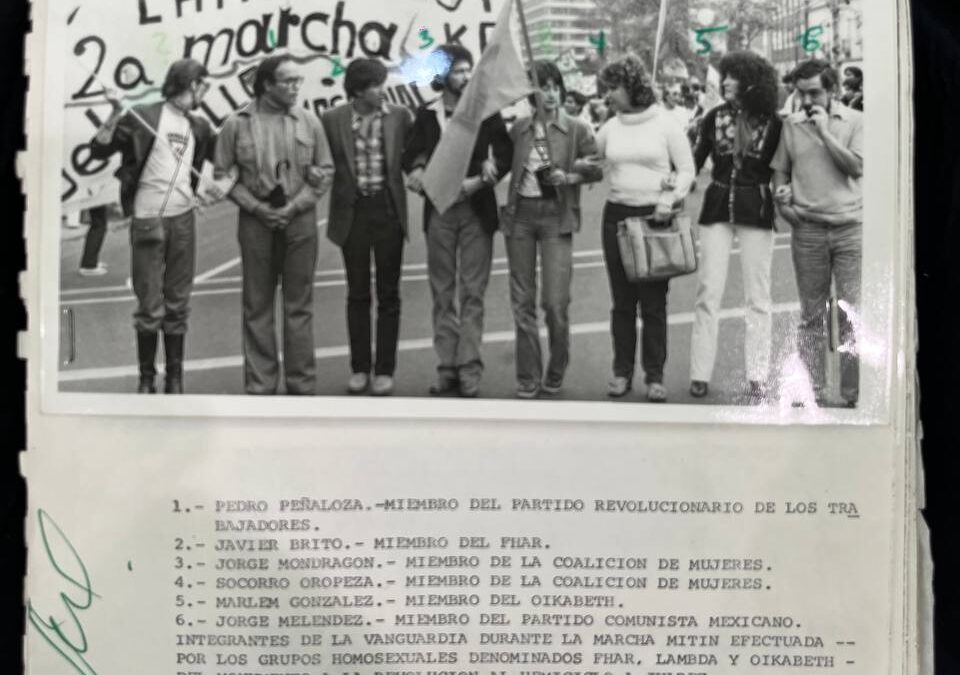

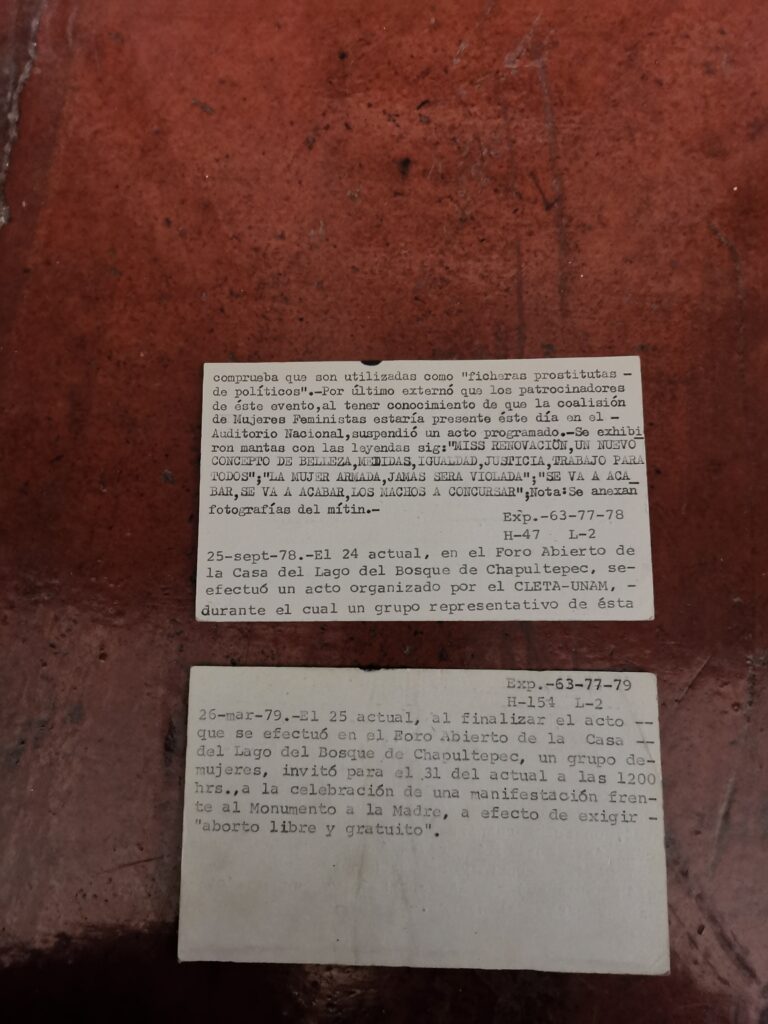

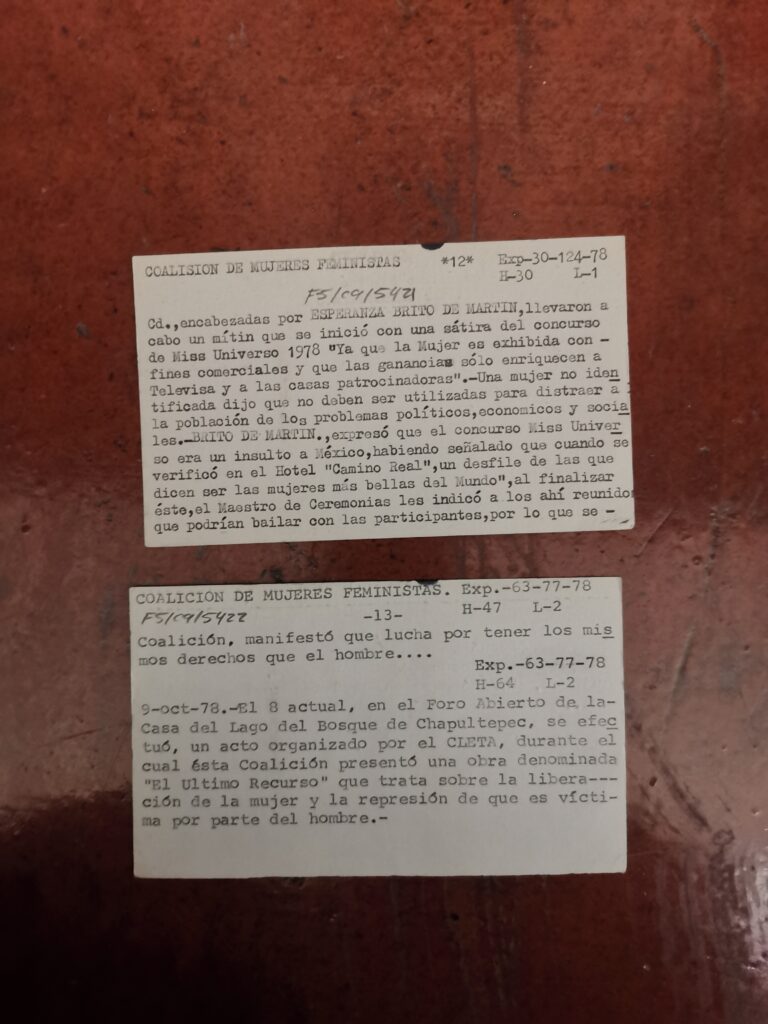

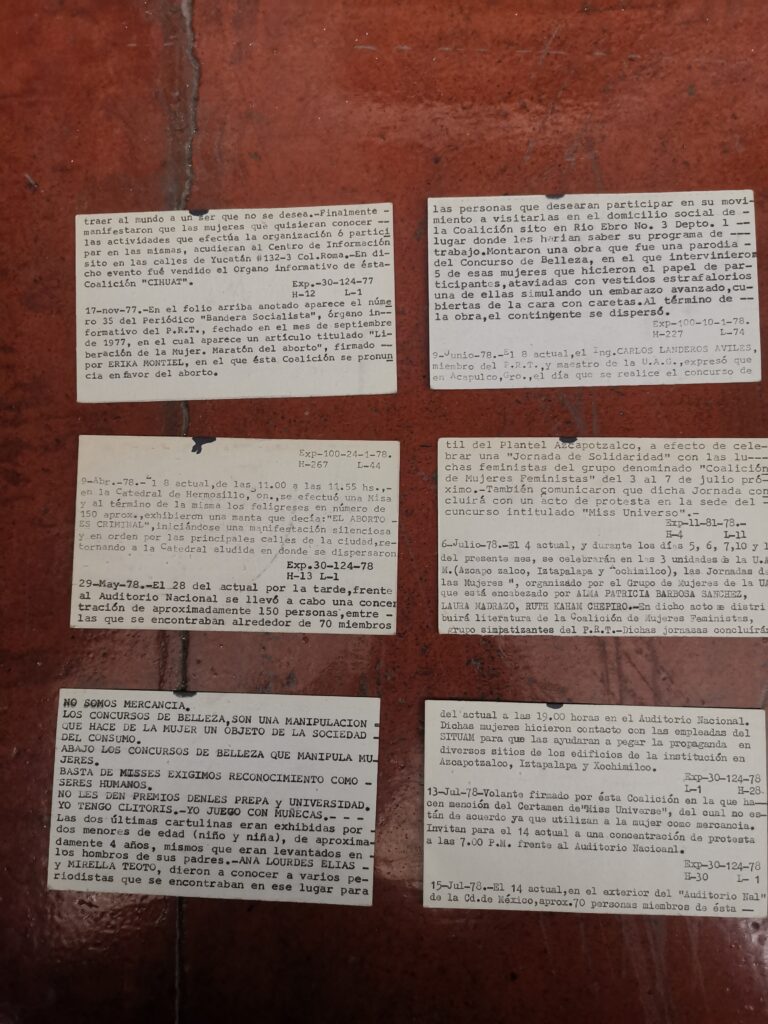

In specific terms, the dossiers collected by the military and police personnel within the security apparatus managed to accumulate 30 profiles of the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas (Feminist Women’s Coalition) , the collective with the highest number of records related to that era. The Coalición de Mujeres Feministas was an organization founded in the early 1970s, of which there are multiple records of their activism, primarily in newspaper archives and libraries throughout the country [2].

As revealed in these reports, the Coalición de Mujeres Feministas was led by two women, Frances Jaime and the journalist from Proceso magazine, Anne Marie Mergier. Military personnel were following their demonstrations, colloquiums, or meetings (whether public or private) with the objective of collecting information related to pro-abortion activism in Mexico.

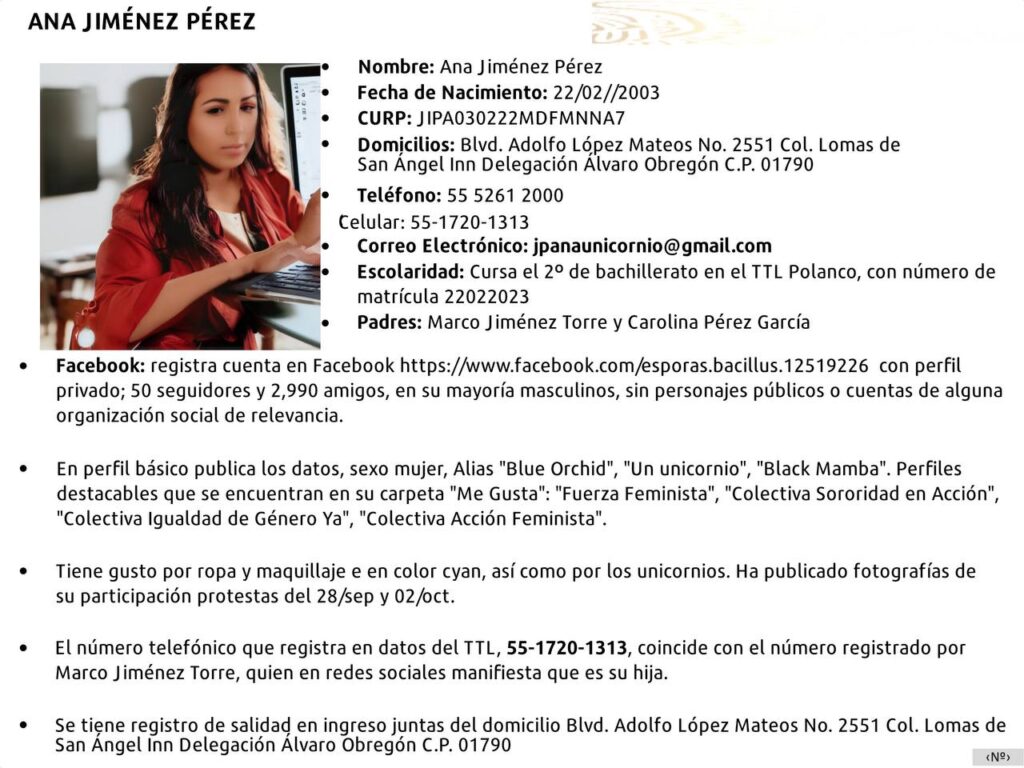

Regarding the information collected by the Secretariat of National Defense, COCE had exclusive access to a report in which personal data of seven profiles that were perfectly interconnected were revealed. The SEDENA presented these profiles to the authorities as a “possible threat.” The collection of these profiles includes their personal information, photographs of their faces, images of their homes, records of their friendships, and social activities (particularly on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter).

However, nothing in the reports suggests that this group could genuinely pose a threat to national security. They are simply women activists, all of them students at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) (National Autonomous University of Mexico), including a minor and a transfeminine individual. The “crime,” according to SEDENA, is engaging in activism in support of women’s rights, in other words, being feminists.

Who were spied on?

Students from the UNAM, academics, researchers, journalists, analysts, and any group or individual whom the Mexican State, under criteria that are neither transparent nor even public, considers as potential subjects of espionage related to “national security.”

The Federal Security Directorate, in general, concentrated its efforts on spying on collectives such as the previously mentioned Coalición de mujeres feministas (Feminist Women’s Coalition), the National Network of Women, the International Lesbian and Gay Association, the Committee of Lesbians and Homosexuals, the UNAM Group, among others. Additionally, the DFS also contains records of some private meetings, and feminist journalists like Anne Marie Mergier are documented in several pages of information with details of their alleged activities as activists advocating for the right of pregnant individuals to access legal abortion.

On the other hand, SEDENA appears to be more interested in specific individuals for whom they record more sensitive information, such as their Federal Taxpayer Registry (RFC), Voter ID number, names of immediate family members and their activities, address, phone numbers, social media accounts, places of assembly, close friends, and professional activities in some cases.

From the DFS to AMLO-era Espionage

As for what happened during the current six-year term, it is impossible to identify the full extent of the espionage. The reports to which COCE had access contain information that jeopardizes the security of the individuals who were victims of surveillance. Therefore, versions are presented that simulate the espionage carried out by SEDENA. Additionally, this discovery is not the only attack against feminist women, but it is the one that most concerned the interviewed activists, especially since it involves underage individuals in some cases.

This attack against feminist students at UNAM occurs in a context where students already feel unsafe due to the institutional environment. The collectives currently occupying the “Foro Che” have expressed concerns about this.

The collective “Estudiantes Organizadas de la Filos” explained in an interview with PODER that one of the most significant problems at UNAM is the growing discourse of hatred against transgender individuals, which, they say, primarily endangers students who identify with genders outside the binary. They also denounce the institutional support and protection of transphobic educators.

According to the statements of the collective, after the appearance of transphobic graffiti at the Faculty of Philosophy, the authorities “turned a blind eye,” meaning they ignored the public attacks on their body of students.

Furthermore, the activists report that UNAM authorities issued a statement requesting respect for the freedom of expression of those attacking this vulnerable group.

“We remember that hate speech is not freedom of expression. Hate speech costs people’s lives. When we said ‘enough of hate speech,’ we received several attacks from unidentified individuals, and currently, the university does not have a viable option for handling harassment cases.”

The organization of women at UNAM emerged at a time when, as stated by the members of the collectives, “speaking out from feminism seems insufficient.” This is because, as they explain, some representations of this movement have consistently expressed positions that lead to acts deemed as violent by the members themselves and exclusionary to others. They specifically refer to transphobic currents within feminism.

Therefore, the biggest barrier between feminist activism and student collectives is primarily the university’s failure to address harassment complaints against hate groups. In other words, even in a context where women activists are spied on by the federal government, they are also forced by the university to protect themselves from attacks by internal, and even institutional, groups. In conclusion, for feminist collectives, “UNAM is a territory where they feel endangered.”

Facebook, UNAM, and SEDENA refuse to be interviewed about the use of their system to spy on activists.

PODER has repeatedly requested interviews with the SEDENA and the communication department of Meta (the brand that owns the conglomerate of companies that make up Facebook) to clarify whether there is any commercial relationship between the social media platform, which also operates as an agency specializing in data collection from its users for commercial purposes and is now being used by the military to criminalize women’s collectives. However, as of the publication of this edition, no employee of the American company has responded. The SEDENA also declined to comment on the matter.

This is not the first time that Facebook has been accused of allowing third parties (companies or military organizations) to access the private data of its users. In 2018, a lawsuit concluded in 2022, with the parent company of Facebook, Meta, having to pay $725 million to a group that collectively sued the social media giant for privacy violations and misuse of personal data.

While the corporation did not admit any wrongdoing, they were compelled to update their privacy terms and allegedly implement a series of measures to ensure that people’s data would not end up in the hands of law enforcement, criminals, or institutions that would misuse it. It is evident that they have failed in this regard.

For this reason, the digital security expert and member of the association Técnicas Rudas (TR) explains in an interview with PODER that it is time to choose more friendly, secure, and collective social networks. “Free software and community organization are the most powerful tools for collective care,” she says.

.

1Los archivos de la represión (2020). Archivo General de la Nación.

2Mediateca INAH (1978). COALICIÓN DE MUJERES Feministas EN LA MARCHA DE HOSPITAL GENERAL.

3Made for minds (12-2022). Facebook pierde demanda por mal uso de datos personales.

__________________

Important:

In Colectivas Organizadas Contra el Espionaje (COCE), more than 240 pieces of documentary evidence from primary sources such as SEDENA, AGN, and DFS were analyzed. Eleven requests for access to information were submitted, and nine interviews were conducted with activists, human rights defenders, and feminist or LGBTQ+ collectives. An interview was also requested with the authorities of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and all other authorities or companies involved, but there was no response. For the security of the individuals who were spied on and out of respect for data protection laws, COCE collectively decided not to contact the civilians who were spied on to ensure their peace of mind and avoid inhibiting their activism.

– This work is a collaboration between Tor Projetc, Técnicas Rudas, Serendipia, Agencia Presentes, and PODER Latam. All the information presented here is freely accesible and has the sole purpose of collective care for human rights defenders and journalists.

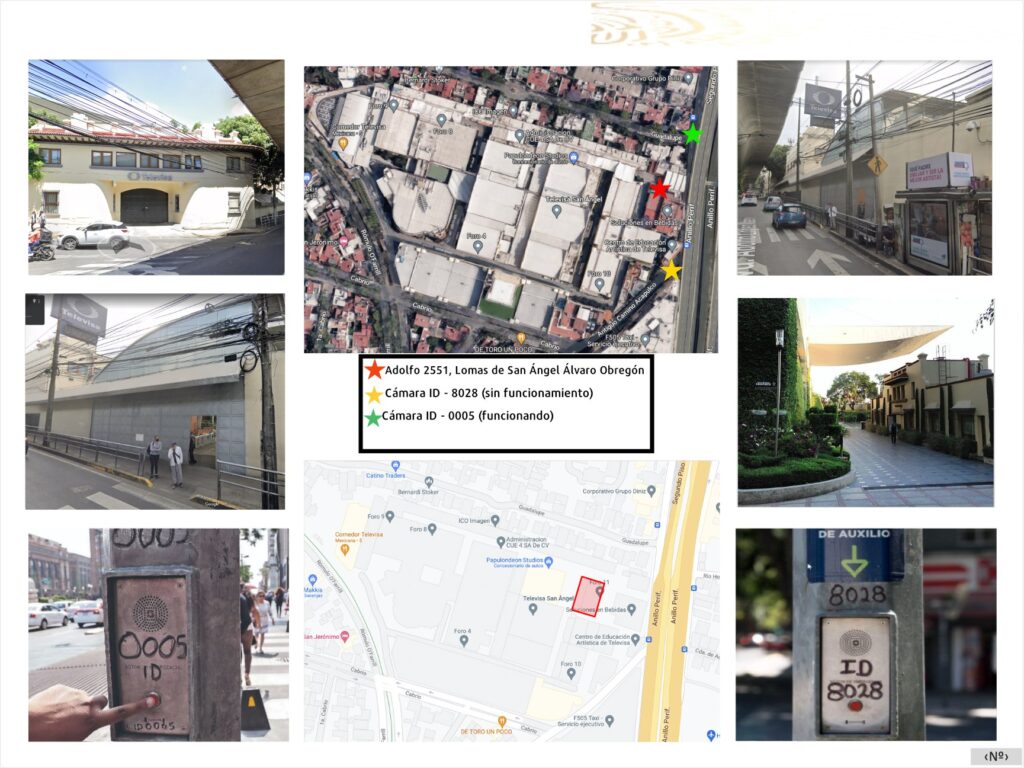

– The information displayed on the profiles is purely illustrative. All data was generated through Open ChatGPT. The map and location photos correspond to the location of Televisa in Mexico City. The building facade photos were taken from Google Maps, and the photos of public emergency cameras are from the https://www.c5.cdmx.gob.mx/ website of Mexico City. The profile photos of the women were generated with DifusionBee.

________________________________

Facebook (META) Response:

1.- The transnational company responds to PODER’s report with the following statement: “We have no agreement with the Secretariat of National Defense to share personal user data as suggested in the report, and we have not shared personal information about our users with them.”

2.-Likewise, PODER requested information regarding data protection policies, what happens when their platform exposes minors to acts of violence, or what occurs when there is misuse (recruitment for organized crime) on the social network, and the response was as follows:

Regarding the other points, I’m sharing these resources:

- Policies on hate speech: https://transparency.fb.com/es-la/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/

- Terms of Service: https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms

- Policies on Dangerous Individuals and Organizations: https://transparency.fb.com/es-la/policies/community-standards/dangerous-individuals-organizations/